Resolving conflict

-

Overview

Overview -

Exercises

Exercises

Overview

In practice: Handling disagreements with confidence, and mediating conflict between others in a way that aligns with expected values and behaviours. Understanding your default mode for dealing with conflict.

“I've learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.” Maya Angelou

NB we use the terms ‘disagreement’ and ‘conflict’ below. They form a spectrum from milder (disagreement) to deeper and potentially more entrenched (conflict) differences of opinion but the principles for dealing with them constructively in most organisational settings are similar. The whole spectrum is covered below.

Feelings about disagreement and conflict

Can you think of a time that you were involved with a disagreement or conflict at work?

Take part in this mental exercise right now. Think of a situation you have been involved in that required you to raise an uncomfortable subject with someone or engage them in a conversation you knew was going to be difficult. What feelings did that engage? Take a few moments and write some down.

Common responses to this question are: unease, anxiety, uncertainty, avoidance, unease, dread, anger, frustration, heart pounding, sweatiness, isolation. Although some people seem to thrive on conflict and seek out situations where they can be confrontational, most of us don’t. At the other end of the spectrum, some of us even find disagreement so difficult that we avoid it at all costs, even though we can see the benefit of ‘robust debate’ sometimes for making good decisions in a team.

In the face of such powerful feelings, how can we best try and move forwards constructively? Fortunately, there are ways to engage with even the most intractable conflicts:

- Understanding your default mode for dealing with conflict.

- Understanding how conflict works.

- Using our step-by-step guide to resolving conflict.

Understanding your default mode for dealing with conflict

Research indicates that the people who are most successful at managing conflict are in the middle of the spectrum mentioned above. They don’t welcome conflict, but they have learnt to face it and don’t shy away from dealing with it when it happens.

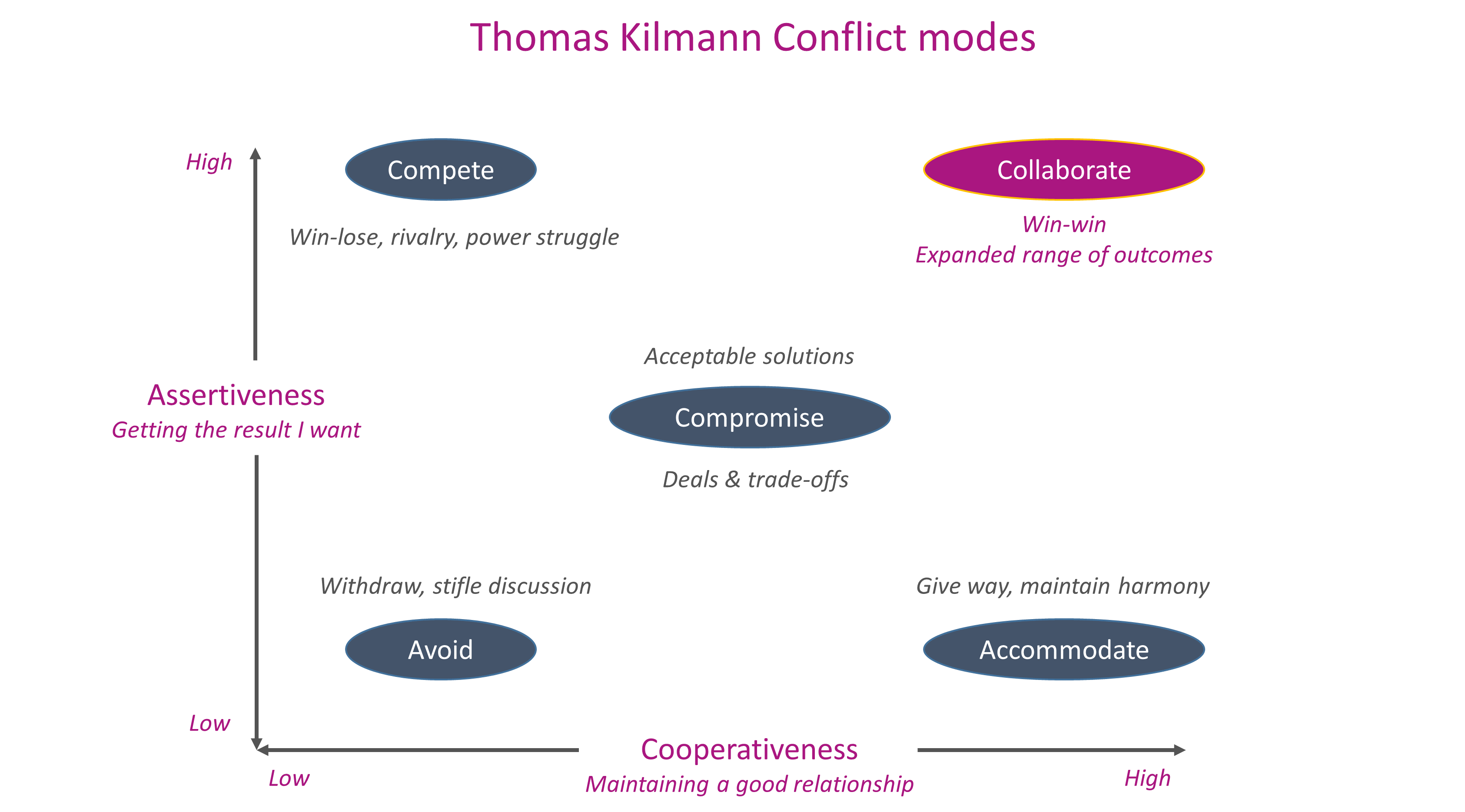

You can discover your own default tendencies in a conflict situation by using the well-known and researched Thomas-Kilmann Instrument (TKI) - see the Exercises tab at the top of the page for more details. The model looks at how focused you tend to be on getting the result you want from a conflict compared with how focused you tend to be on maintaining a good relationship with the other party:

Once you understand your own and others’ basic conflict styles you can work on your own approach to help you handle disagreements with more confidence and mediate conflict between others.

So, a good starting point is to understand (and maybe modify) your own preferred ‘style’.

Understanding how conflict works

There are certain common features of difficult conversations / conflict.

- Both people think they are right.

- Both people’s conclusions make sense to them.

- Neither person’s conclusions make sense to the other person.

This occurs because:

- We are likely working from an overlapping, but different, set of facts about the issue.

- We make assumptions about other people’s interests and needs. These assumptions may well be wrong. (see the PIN model below)

- At times of heightened emotion, we can easily mis-understand each other’s words and actions. (See the Communication awareness matrix below)

We run through below a step by step process used by professional mediators to resolve conflicts, but first we need to introduce (a) the PIN model for understanding other people’s interests and needs and (b) the Communication awareness matrix, which will help us reflect on the gap that can exist between our intentions of our words and actions and the actual impact they have on others. Doing the PIN model and the Communication awareness matrix exercises (see the tab at the top of the page) will also help you to make the most of ‘Step-by-step guide to resolving conflict’.

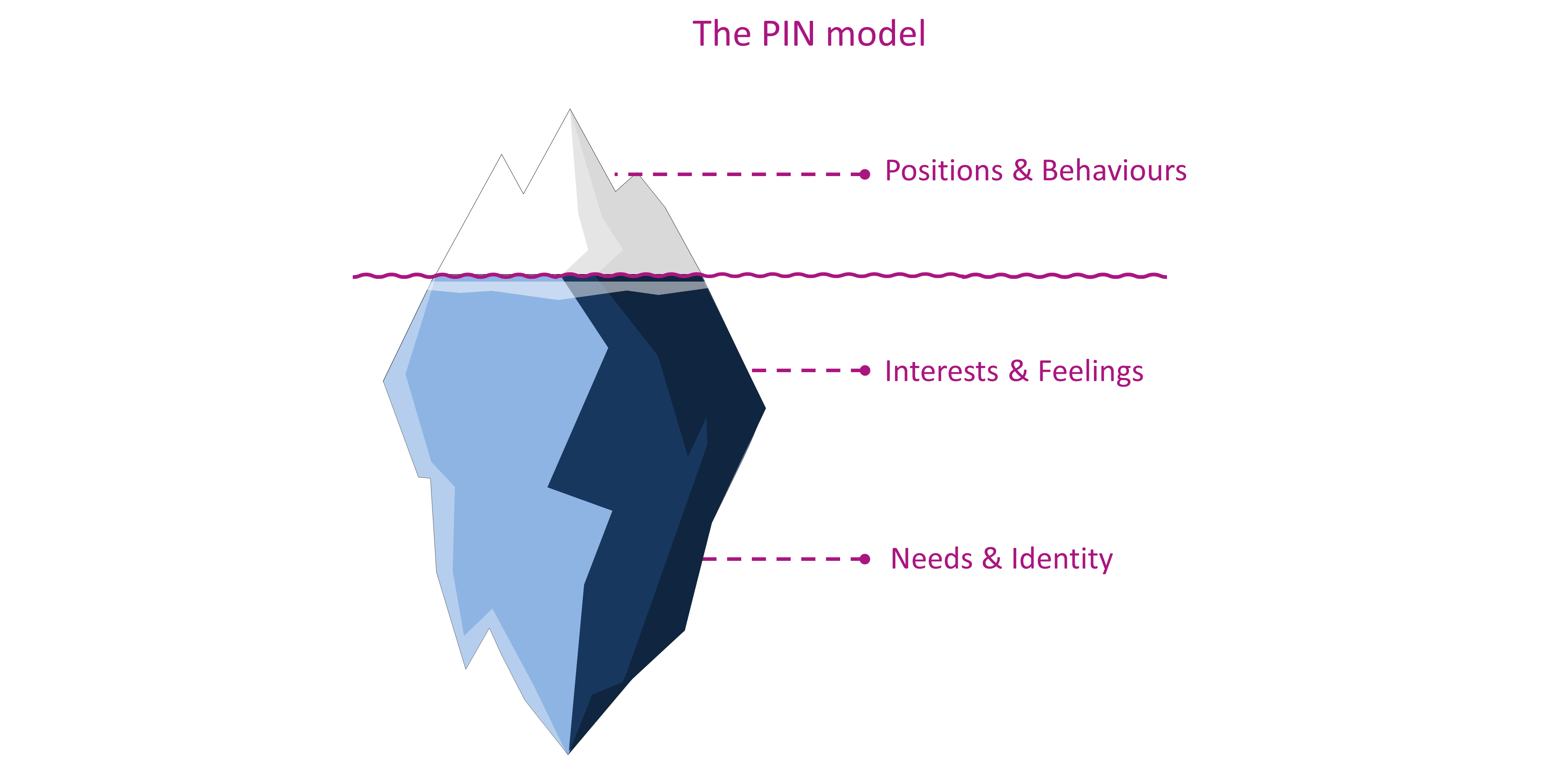

The PIN model

Mediators refer to the ‘PIN model’, which stands for Positions, Interests and Needs. Positions are visible to the outside world (the top of the iceberg) while Interests and Needs are hidden below the waterline.

- Positions are what you see - a person’s spoken works, actions and behaviours.

- Interests are what they think they’re going to achieve by adopting the Positions that they have.

- Needs are what is driving that person’s behaviour from a deep level. Needs can be (for example) physical (if I lose my job, I can’t pay for my mortgage, I’ll lose my house, etc), psychological (this conflict is exactly how my father used to treat me), existential (if I lose this conflict, I am at risk) or something else entirely.

You can find an exercise on how to use the PIN model here.

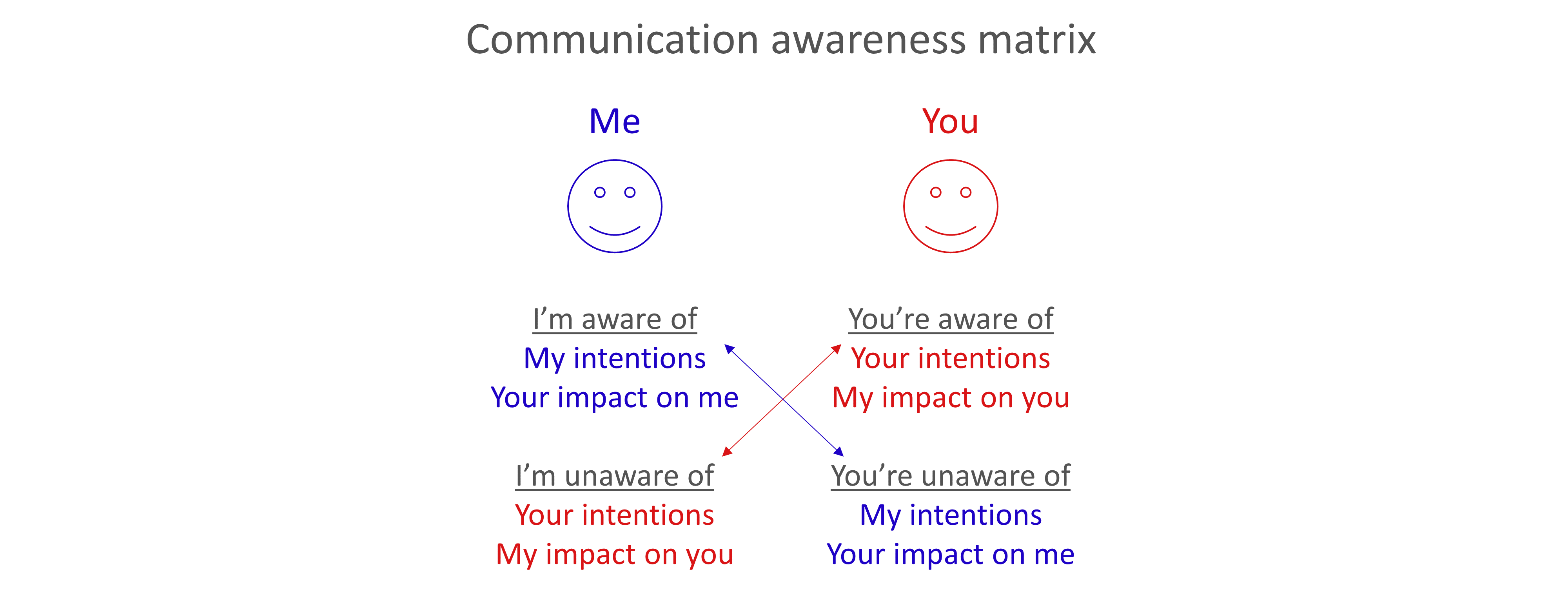

The Communication awareness matrix

In conflict, we bring the other person’s behaviour into sharp focus. We notice what they do, what they say, how they behave. And key to this: we make assumptions about their motivations and intentions based upon their negative impact on us. We interpret a brief email as rude, whereas it was hurried because the person wanted to let us know something quickly. The intention was to be helpful but the impact on us was to make us feel offended. We are aware of our own intentions and the impact others have on us but may not be so aware of others’ intentions or the impact we are having on them. However, we act at times like there is no distinction between the two sides of the diagram below.

Reflect on your own awareness of what you might be assuming about the other person when in a conflict by taking this exercise.

Step-by-step guide to resolving conflict

The aim for successful conflict resolution is to shift two parties away from an “I’m right, they’re wrong” argument into a joint problem-solving approach. Professional mediators encourage the parties to follow the following four step plan which can be used whether you are trying to mediate a conflict between two other people or you are one of the parties in the conflict you are seeking to resolve. Bear in mind from the PIN model and the 'communications awareness' matrix that the discussion is more likely to be fruitful if:

- Each party understands the other party's interests and needs, not just their positions, and

- You seek clarification about the other party's intentions, words and actions rather than jumping to conclusions about them

With that in mind, the four-step process is:

Step 1: Establish a safe conversation.

A safe conversation is “one in which both parties feel comfortable expressing their thoughts and feelings without negative ramifications and without feeling threatened”.

To make a conversation safe:

- State that you want to work together to understand each other’s perspectives and to see how best to resolve the issues and move forward – not to apportion blame.

- Acknowledge that you consider their perspective to be legitimate, and that you hope they are able to understand your perspective too.

- Accept that the conversation may not be easy, but that you are looking to try and make things better for everyone.

Step 2: Listen and Explore

Remember that the other person won’t start to listen until they’ve felt heard.

Explore the other person’s perspective on what is going on. Get them talking about their perspective and enquire with genuine curiosity about how they see the situation. You are looking for insight into what their Interests and needs might be. This is not just ‘fact-finding’. The conversation will also build trust and cooperation if you are aware of predictable emotional concerns that people have in negotiations – the need to feel appreciated rather than demeaned, to be treated as a colleague rather than an adversary, to feel autonomous rather than controlled, and to be respected.

Don’t expect to agree. Compel yourself to listen without interruption or judgement, give people space and let them do the talking. The key test: you shouldn’t be doing most of the talking.

Step 3: Dig Deeper

If you are listening well, you will start to pick up on what’s important to the other person.

Use can use questions such as these to try and get to the heart of what is happening:

- What impact is the situation having on us and others?

- What do you think needs to happen for us to be able to move on?

- What do you hope to get out of this discussion?

Once you have identified what you think is important, reflect it back to the other person to check you’re your understanding is right(e.g. it sounds to me from what you’ve said that [x] is particularly important to you. Have I heard you right?).

You can also invite the other person to adopt the ‘Mediator’s view’: If you were on the outside looking in here, what would you think about what’s going on? Can you both step outside of the conflict and look for solutions together?

Step 4: Find common solutions

You are ready to move to this step when you have got everything that is important to both parties out on to the table. If you haven’t, the parties won’t have felt heard, and they’ll go back to ‘their story’.

Check where you are by asking: ‘if I can summarise what I’ve heard, you’re [summarise, using their words if possible]. Is that what you think is at the heart of this? Have I missed anything?’

If both parties say the summary reflects the position accurately you start to can explore solutions together.

Research shows that the biggest barrier to successful conflict management is the “I win, you lose” approach. Win-win conflict resolution turns a heated disagreement into a search for a solution that makes both parties happy

Tip: It’s common to have a view as to the ‘best fit’ solution. Beware this trap: what appears obvious to you might not be right for the other person. Generate solutions together, using the other person as the primary source.

The key starting point is to agree the overall results you both want. This will give both parties some criteria to assess whether a proposal is a good solution to their disagreement.

If you can do that, you then move to creating some “win-win” possibilities. These are possible ways forward that take the underlying interests of the two parties and create suggestions that help both sides to get more of what they want. It involves both sides really listening to each other to work out ways of maximising the overall cake.

Win-win solutions are different from compromise. Compromise usually involves agreeing on the lowest common denominator – a solution that causes least offence to either side - or agreeing a trade-off where one side sacrifices something it wants in return for a corresponding sacrifice from the other side.

Finally, If you can, agree specific goals for the next steps to move forward and whenyou will meet again to review progress.

Exercises

Exercise - Discovering your approach to conflict with the TKI

The Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI) is a well-known way of understanding your approach to, and feelings about, conflict

Exercise - PIN Self Audit

Using the PIN model to reflect on what a particular conflict means for you and how you might modify your approach to the conflict to increase your chances of success.

Exercise - Communication Awareness Exercise

Helping you to reflect on assumptions you are making about someone, and how to check out if they are correct.

Exercise - Robust debate vs joint problem-solving

This exercise will help your team find the right balance between robust debate and collective problem-solving.

Exercise - Resolving conflict

The aim of this exercise is to help you turn conflicts into joint problem-solving discussions.