Team innovation

-

Overview

Overview -

Exercises

Exercises

Overview

In practice: Enabling your team to respond flexibly to mistakes and see them as learning opportunities in order to create improvements.

Research on over 2000 teams in our database indicates that the ability to innovate and deliver change effectively is central to the best performing teams.

Teams who can use mistakes, as well as successes, as opportunities for learning usually outperform less learning-focussed teams1 . They are more agile and are more on the look-out for important changes in their environment such as changes in customer requirements. By combining a high external focus and an innovation-friendly culture these teams can respond flexibly and effectively and take advantage of opportunities. In our database these teams get the highest ratings from their stakeholders and customers.

We focus here on how to build an innovation culture for your team. Other articles on this website will take you through relevant topics like:

Reframing ‘failure’

The baseline conditions for a team to innovate well are that its members should not be afraid to make a creative contribution, however ‘unusual’, and the team as a whole should feel able to experiment.

The challenge is that when things don’t go according to plan – which inevitably happens with some, if not most, innovations – the words ‘failure’ and ‘blame’ are never far behind.

But how many ‘failures’ in organisations are actually blameworthy? Amy Edmondson, Harvard Professor and leading expert in how to make teams feel ‘safe' for learning and innovation, categorises failures thus:

- Preventable

- Deliberate violation (Blameworthy)

- Inattention (Maybe blameworthy)

- Lack of ability (Unlikely to be blameworthy)

- Complex

- Inadequate or faulty process (Not blameworthy)

- Task too complex to guarantee success every time (Not blameworthy)

- Intelligent

- Trial with an uncertain outcome (Not blameworthy)

- Experiment (Not blameworthy)

Edmondson often asks teams (a) to estimate what percentage of the failures in their organisations might be caused by blameworthy actions. Usually, they pick a number that is less than 5 percent. Then she asks them (b) how often failures in their company are actually treated as blameworthy. After a pause (or an uncomfortable laugh), they come up with a much higher number, say 70 to 90 percent, which, if accurate is guaranteed not only to stifle innovation but also to crush learning in a team.

You might like to look at the lists above and ask yourselves the same questions. (For more details see the Exercises tab at the top of the page).

A team that easily shifts to blaming will be more likely to block the flow of creative ideas:

The fears that block people’s creative ideas have been summarised by the Stanford Professor who founded IDEO2 as:

- Fear of the unknown – needing to shift from the comfort of the office to the messy unknown of asking customers how they might react to an as yet undesigned product.

- Fear of the first step – prevaricating because you are unsure where to even start.

- Fear of being judged – wanting to protect our ego from what other people may think.

- Fear of losing control – concern that the team may take over your precious idea and change it out of all recognition.

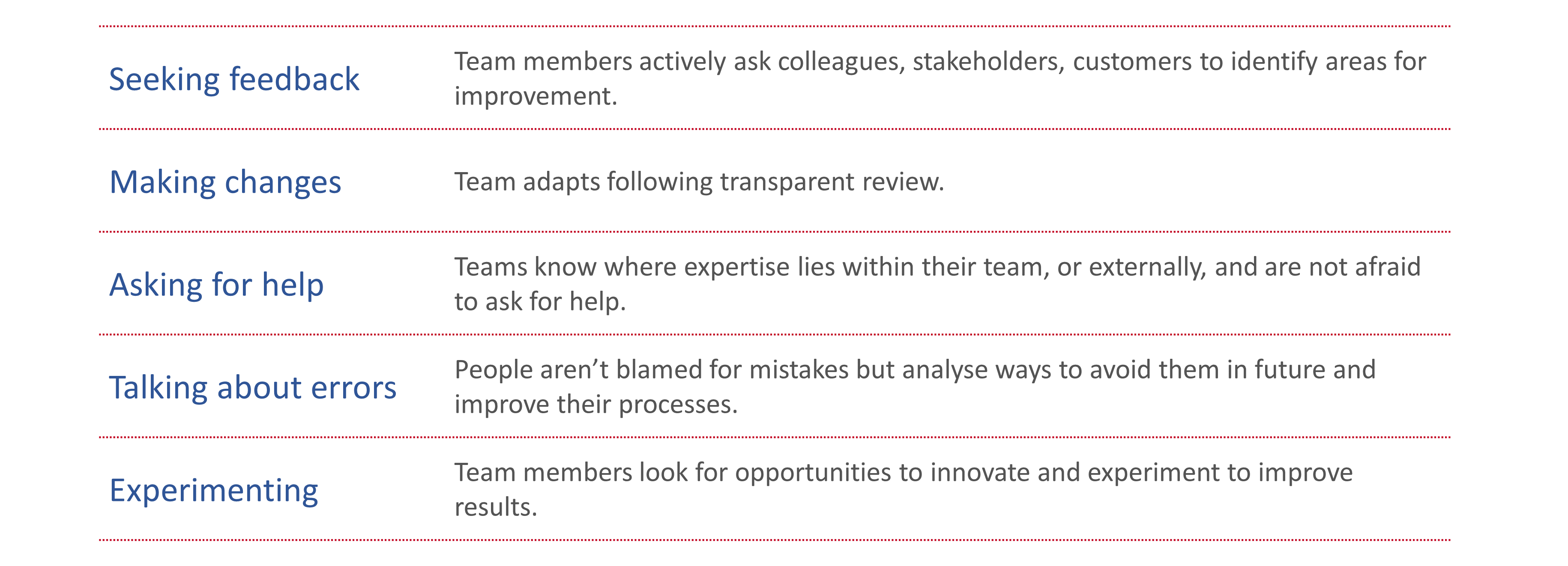

What can a team do to avoid this situation? Here are five ways of working that help team to overcome a 'blame' culture3:

Safe team learning

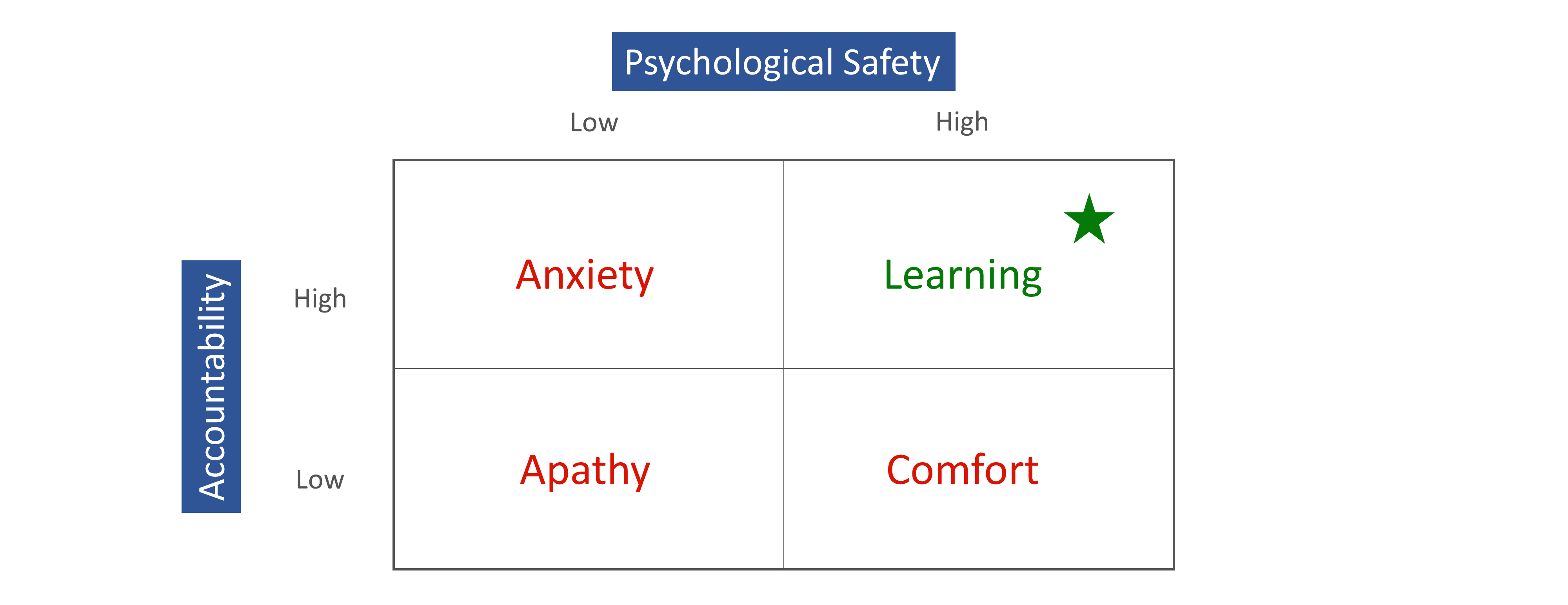

Learning as a team requires an environment where every team member feels psychologically safe. This means team members feel confident that the team will not embarrass, reject, or punish them for speaking up, as people tend to act in ways that prevent learning when they face possible threat or embarrassment4.

Team psychological safety doesn’t mean lack of accountability or standards. It is possible to work in an environment that is neither safe nor properly accountable; it is also possible to work in a psychologically safe environment that encourages every team member to feel accountable to the team as a whole5.

In fact, a ‘high accountability – high safety’ team culture provides a perfect context for high team performance and innovation, as we will see in the next section on Agile innovation.

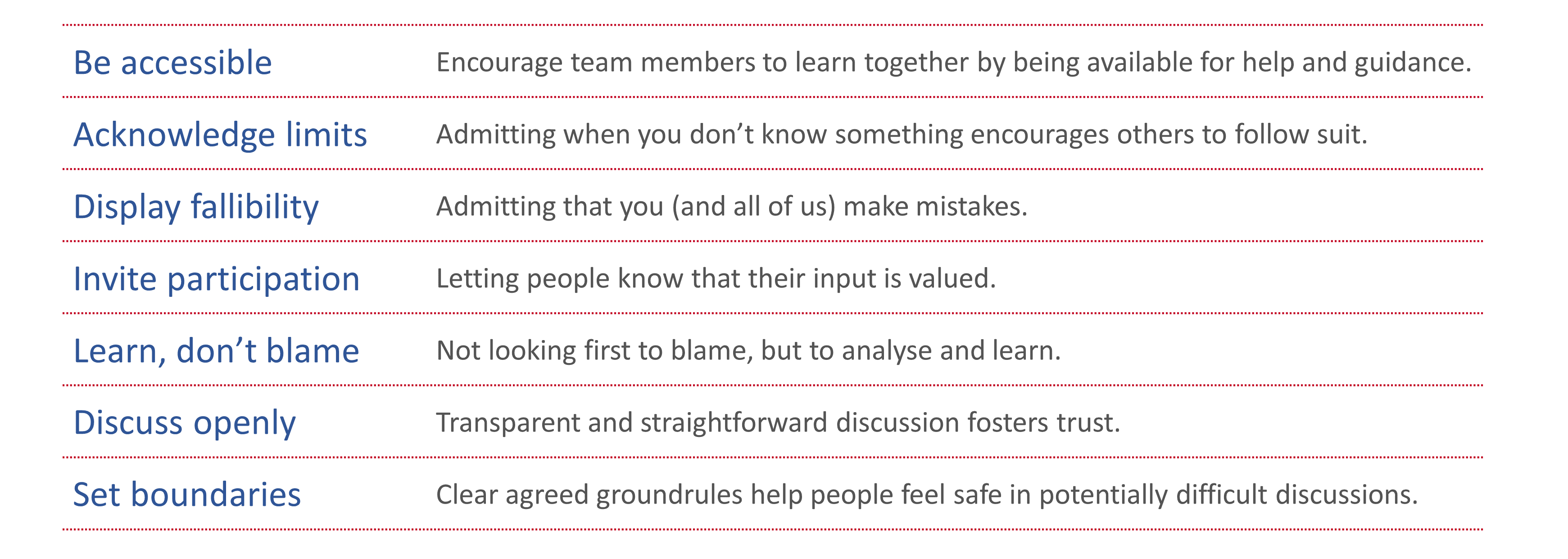

Improving your team’s trust and psychological safety relies on a concerted effort. It is part of the role of an effective leader to role-model trusting and psychologically safe behaviour, and to help reinforce similar behaviour in the team. Some typical ways recommended by Edmondson6 for doing this are summarised below:

Research has shown that ‘cross-training’ (a process involving team members spending time to become more familiar with each other’s roles) is a very effective way to build trust and increase understanding, communication, and coordination between team members7 . A variety of ways of approaching this is shown in the Exercises.

For many teams, improving team learning means a significant culture change – a change that the evidence shows is worth the time and effort.

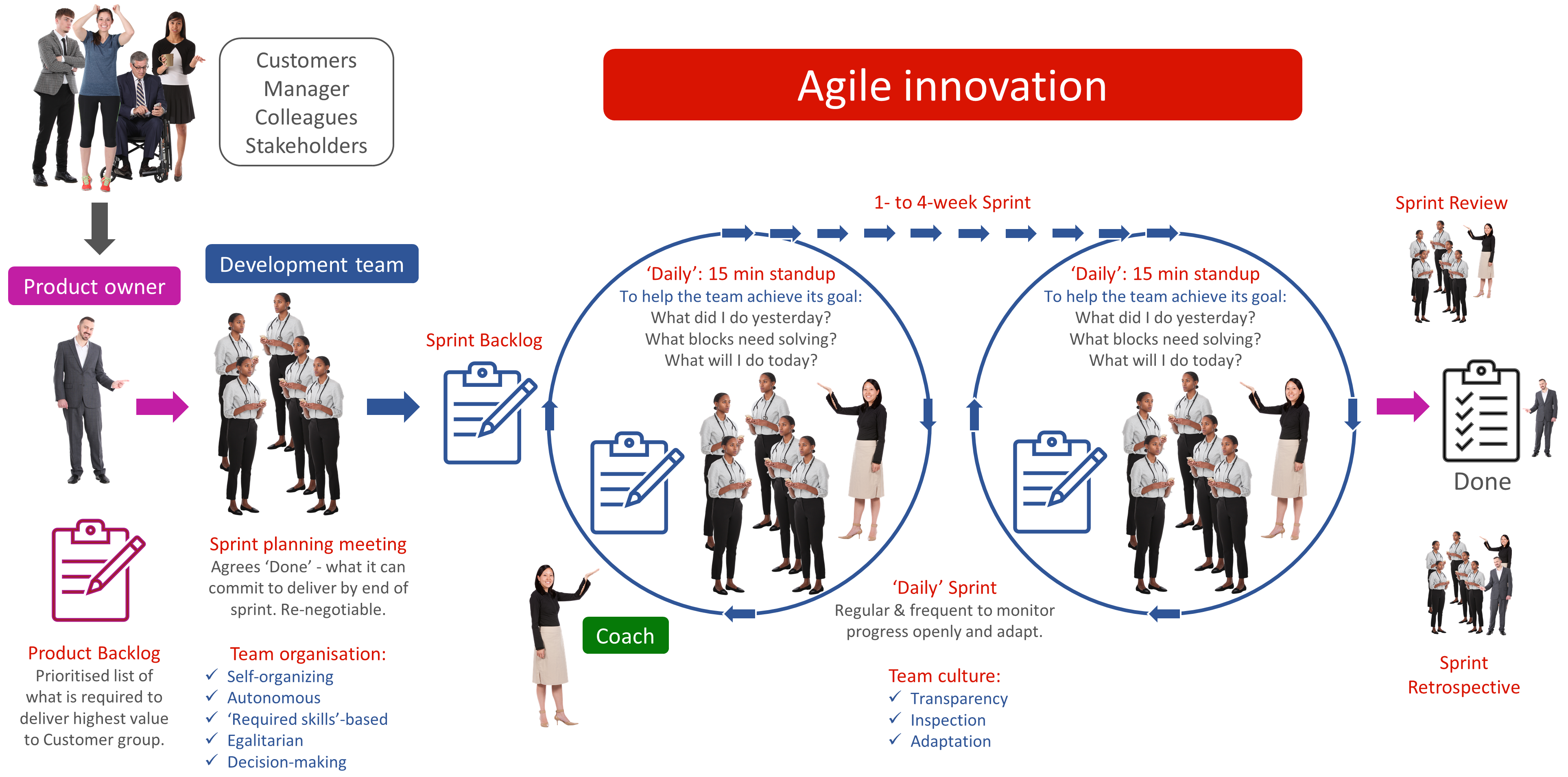

Agile innovation

With the fundamentals in place – a culture where people feel safe to contribute, where there can be healthy discussion, resolution of disagreement and where ‘failure’ does not automatically lead to someone getting blamed – we can now look at a team model for innovating in a systematic and speedy manner. It builds on, indeed requires, a culture of transparency and straightforward discussion of all and any issues.

The Agile Manifesto8 was published in 2001 as a better way of developing software at a time when IT projects were often delivered late, were bug-ridden and didn’t meet customer requirements. Since that time Agile, and its sister frameworks of Scrum and Kanban have spread outside IT and software development9 and represent a culture and way of thinking that enable but de-risk innovation by fully empowering development teams and encouraging continuous adaptability alongside scrupulously honest discussion of what’s working, what isn’t and what needs to be done to improve.

The Agile Manifesto and The Scrum Guide10 contain useful specifics and principles of their approaches. To generalise, they consist of:

- A focus on staying close to what the ‘customer’ of the innovation requires – by building tangible improvements in small increments and receiving frequent feedback from the customer. (‘Customer’ is used as a broad term here to include stakeholders, colleagues, patients etc).

- Self-organising, autonomous teams.

- Regular and frequent ‘review and improve’ team meetings (known as ‘Daily Scrums’ but this can be tweaked to fit the project rhythm) based on open, honest discussions about what the team needs to continue with, adapt or stop to deliver successfully. These are based on feedback and adaptation cycles derived from process control methodology.

- Continuous improvement driven by a constant learning culture.

For example, Scrum is built on three pillars of:

- Transparency – requiring a shared understanding of the aim of “Done” (what it means for a piece of work to be complete).

- Inspection – frequent monitoring and collective discussion of progress.

- Adaptation – adjustment to minimise deviation from the team’s agreed workplan.

Scrum team values build trust11 :

- Commitment to achieving the goals of the team together.

- Courage to do the right thing and work on tough problems.

- Focus on the team’s work and goals.

- Openness of the team and all stakeholders about all the work and the challenges with performing the work.

- Respect for each team member to be capable independent people.

Work is organised in short cycles (“Sprints”) and in teams: (i) the self-organising autonomous egalitarian “development team” who decide how to deliver, and do deliver, the Done work and (ii) the Scrum team - comprising of the development team plus the Product Owner (accountable externally to the ‘client’ and for setting the goal of the Sprint) and a process expert / facilitator called the Scrum Master.

The Sprints themselves have a time-boxed rhythm to them with:

- An initial Sprint Planning session.

- Short ‘Daily’ (ie regular & frequent) Scrums that inspect progress and re-prioritise work.

- Sprint Reviews that inspect outcomes at the end of the sprint.

- A Sprint Retrospective that inspects team processes and agrees improvements.

These Agile / Scrum processes promote team learning and improve team innovation. They are consistent with the self-regulated learning and guided mastery models that are known to improve learning and enhance feelings of self-efficacy in adults. The focus on autonomy rather than external control is better for us as individuals, better for us in teams and better for the organisations we work in.

1. Edmondson A., 2013, Teaming to innovate, John Wiley and Sons

2. Kelley, T. and Kelley, D. 2012, Reclaim your creative confidence Harvard Business Review, December 115 - 118

3. see Edmondson A., 1999, Psychological safety and learning behaviour in teams, Administrative Science Quarterly 44(2) 350 - 383

4. ibid

5. Edmondson, A., 2019, The fearless organization: creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth, John Wiley and Sons.

6. Edmondson, 2013 op. cit.

7. Marks, M et al 2002, The Impact of Cross-Training on Team Effectiveness, Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 1, 3 - 13

8. See agilemanifesto.org

9. See https://www.scrumalliance.org/learn-about-scrum/state-of-scrum

10. Schwaber, K and Sutherland, J , 2017, The Scrum Guide

11. ibid

Exercises

Do you fix the blame before the problem?

A good way of assessing whether you have a blame culture in your team - or whether, as an individual, you may be too quick to attribute blame.

Exercise - Giving feedback in a team setting

The aim of this exercise is to help you give more constructive feedback to other people.

Rapid review of any team activity

Two questions you can ask yourself about any activity you have undertaken - as a team or individual

Cross-training in a team

5 exercises, in increasing levels of time commitment, to help team members understand each other's tasks, priorities and pressures